Bloomberg Ticker: FNFACA

First Nations Finance Authority (‘FNFA’ or ‘Authority’) was built on a robust planning

framework that spanned more than 20 years in development. The process originated with

meticulous federal government policy research, and eventually led to the enactment of

supportive and protective legislation that underpins sound financing practices. This framework

ensures the utmost protection for bank lenders and bondholders. The framework establishes

clear parameters which gives First Nations communities access to capital for important

infrastructure and business development.

Canada’s First Nations have made strong progress over the past decade in securing their

entitlement to share in the financial benefits of Canada’s natural resources, and asserting

their rights to be consulted on major energy and resource projects. First Nations and

Canadian government relations at all levels are being re-set on a course of stronger

understanding and cooperation to secure a brighter and better future for all Canadians. To

this end, FNFA is an important funding platform that harnesses the capacity of the institutional

capital markets to participate in this journey. There are currently 200 First Nations out of 634

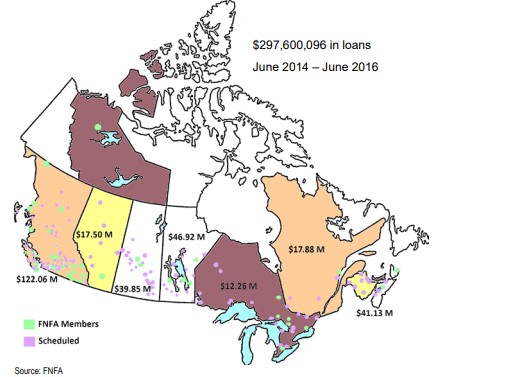

across Canada scheduled in the program. FNFA projects its loan program to grow from

approximately $297mln today to over $1.2bln by 2021.

“Resetting the relationship and affirming First Nation rights and First Nation government

responsibilities to their people can unlock economic potential, and generate significant and

essential opportunity for all Canadians,” stated Shawn Atleo, former National Chief of the

Assembly of First Nations.

Dr Dominique Collin is a former senior economist with the Government of Canada

(Department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, or ‘INAC’), and is now

Principal of Waterstone Strategies, a private consulting firm.

A quote from Dr Dominique Collin:

I have been involved in Aboriginal access to capital issues for 30 years, from

the federal government side and from the Aboriginal financial institution side,

and in all that time I have not come across any instance of First Nation

governments defaulting on long-term infrastructure or public work-related

debt. Social housing debt, the single largest block of First Nation

government debt, has been an important feature of First Nation government

finances for more than a generation, most of it with federal government

backstop. The published loss rates for government housing backstop

programs are close to nil, as confirmed by a sequence of Auditor General

reports on Aboriginal housing, confirming that First Nation governments are

a good lending risk.

Over the past 10 years, a rapid increase in own-source revenues from

benefit agreements, royalties, revenue sharing agreements, participation in

major energy, and resource projects has multiplied the capacity of First

Nation governments to address business and infrastructure investment

needs with debt. Setting aside community-owned business ventures, which

on the whole have done well but remain within the business risk category, I

am not aware of any defaults. This likely results from the solidity of the

revenue streams used for borrowing, the increased ability of lenders to

understand the lending environment and, most important, from the

willingness of revenue-rich First Nations to opt into rigorous financial

administration oversight regimes such as the one provided by the First

Nations Financial Management Board certification process.

Dr Collin has been involved in a number of Aboriginal financial institution development

initiatives in the areas of business, infrastructure and housing finance. He is the coauthor, with Michael Rice, of Access To Capital for Business: Scoping out the First Nation and Inuit Challenge, an in-depth analysis of Aboriginal access to capital

performance and issues from 1975 to 2003. An update of this report to 2013, with an

analysis of the 10-year increase in outstanding business/infrastructure debt, will be published in the fall of 2016.

An example of an FNFA loan is the $5.27mln, 30-year term loan to fund the Songhees

Wellness Centre in Victoria, British Columbia (shown below), which is backed by a federal 20-

year Right-of-Way contract giving a Canadian naval base road access through lands owned

by the Songhees First Nation.

The Songhees Wellness Centre, Victoria, British Columbia

Topics Covered, by Section:

- Debt Issuance, Valuation and Portfolio Placement

- Legislative Framework, Lending Approach and Bondholder Protections

- Credit Underwriting Process and Experience

- Financial Reporting and Transparency

- Canada’s Political System and First Nations

- History of Canada’s First Nations

Debt Issuance, Valuation and Portfolio Placement

First Nations Finance Authority

FTSE TMX Canada Universe Bond Index Classification

- Sector: Government

- Industry Group: Municipal

- Industry Sub-Group: British Columbia

- Rating: A

- Index Weight: Less than 0.5%

Regulatory Classification: - Basel III Risk-Weighting – Standardized Approach*: FNFA is a non-share, nonprofit corporation and may meet the criteria for a ‘Claim on Corporate’ with a

credit assessment rating of A- to A+. Under this criteria, bonds would be subject

to a 50% haircut. Investors are advised to consult their legal counsel. - HQLA – OSFI Liquidity Adequacy Guideline/Basel III: FNFA is a non-share, nonprofit corporation and may meet the requirement of a Level 2B asset (50%

haircut). Investors are advised to consult their legal counsel.

*FNFA is not classified as a Public Sector Entity (PSE) for purposes of the

Capital Adequacy Guidelines. Chapter 3.1.3 of the guidelines provides that

where PSEs other than Canadian provincial or territorial governments provide

guarantees or other support arrangements other than in respect of financing of

their own municipal or public services, the PSE risk weight may not be used. The

PSE risk weight is meant for the financing of the PSE’s own municipal and public

services.

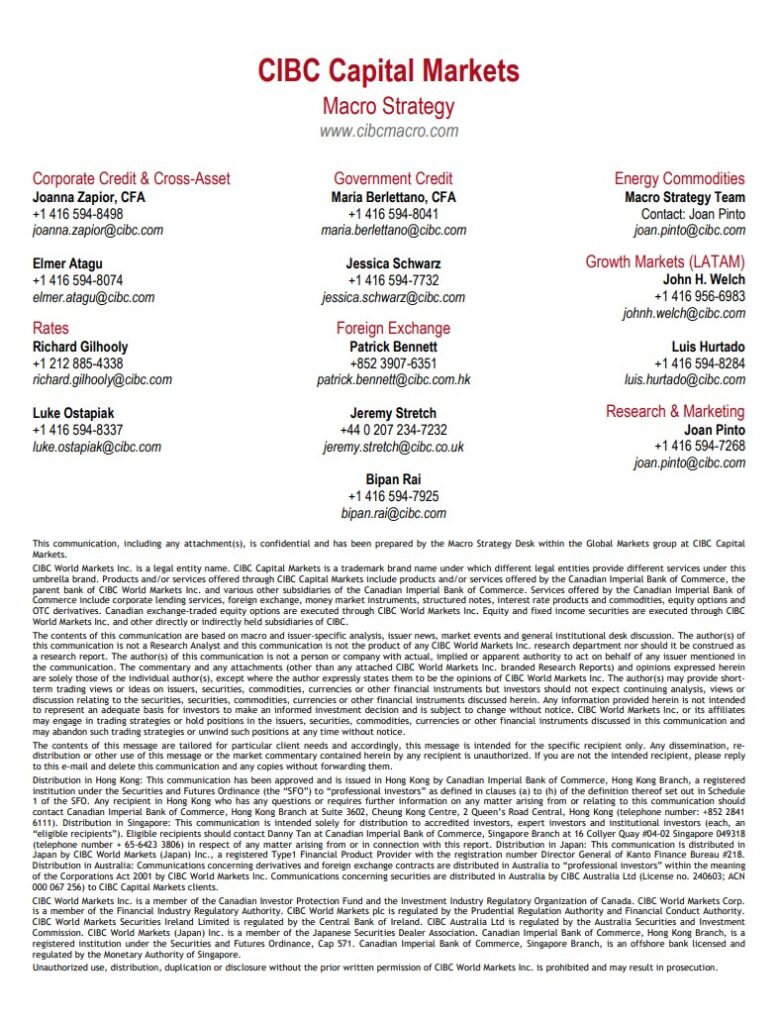

First Nations Finance Authority began funding in the institutional debt markets in June 2014

with its inaugural 10Y issue of $90mln (FNFACA 3.4% June 26, 2024). Since 2014, the

Authority has tapped the market once a year by upsizing the existing issue twice.

Going forward, FNFA is planning to continue targeting the 10-year funding area. It expects to

issue $130mln annually for next two fiscal years as the client base increases. In the third

fiscal year, it anticipates doing both spring and fall issuances, aggregating about $250mln in

each fiscal year.

FNFACA 3.4% June 26, 2024 $251mln – S&P Rating A- Moody’s Rating A3 Stabl

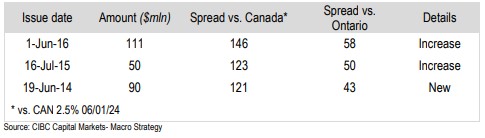

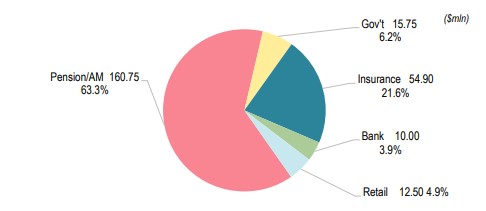

Like other government issuers, FNFA raises debt in the exempt market by offering securities

via an Information Memorandum. The Authority has historically borrowed through a

syndicated market process. There are 20 to 25 investors currently participating in FNFA’s

debt issues, crossing all investor types. While the majority of investors fall into the category of

large Canadian institutionals, there has been a modest level of Canadian retail participation.

There has also been a good level of participation by US investors. The most recent

transaction was distributed to 22 institutional investors, with an overall blend of almost 50/50

between repeat and new, as the investor base continues to grow.

Debt Issuance by Type

Source: FNFA, CIBC Capital Markets – Macro Strategy

Debt Issuance by Location

Source: FNFA, CIBC Capital Markets – Macro Strategy

FNFA bonds are classified in the FTSE TMX Canada Universe Bond Index in the Municipal

sub-sector category. Like other Canadian bonds in this category, FNFA bonds are best suited

in investment portfolios as ‘buy-and-hold’ positions in passive mandates, as well as a

component of active mandates. They also have broad appeal in retail accounts due to their

investment grade quality and name familiarity. FNFA bonds may also be suitable for holdings

by regulated financial institutions.

The municipal sub-sector represents about 2% of the FTSE TMX Canada Universe Bond

Index, and we are constructive on a ‘modest’ overweight position (3-4%) at current spread

levels, and a position in FNFA bonds towards an overweight.

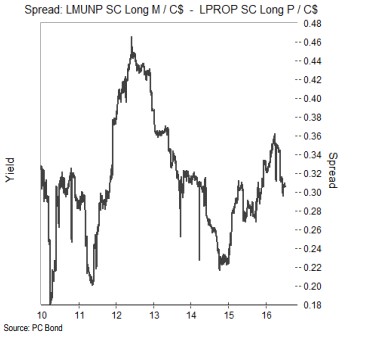

In spite of the generally stronger credit risk profiles of municipal bonds, these types of bonds

trade back of their more senior provincial counterparts and generally move in tandem. As

depicted in the spread graph below, earlier in the year, municipal spreads moved wider than

their provincial counterparts (i.e. basis risk) reflecting a global re-pricing of liquidity premiums

that was spurred by extreme market volatility and risk aversion. Spreads have since tightened

somewhat, but the liquidity spread premiums remain attractive in the current low interest rate

environment where investors are searching for yield.

It’s important to highlight that secondary market liquidity continues to be impinged upon by

regulatory requirements imposed on financial institutions and their broker/dealers. Moreover,

a trend towards dealer inventory aging requirements is also having an impact.

Long Muni Index Spread over Long Provi Index

We like FNFA municipal bonds as a means to anchor portfolio credit quality (Moody’s A3,

Standard & Poor’s A-, all outlooks ‘stable’) and for yield pick-up. We expect FNFA’s credit risk

profile to be relatively stable, and improve over time.

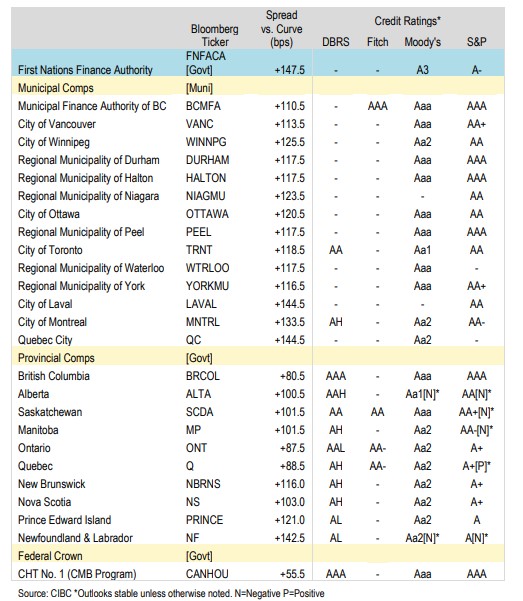

10Y New Issue Indicative Bond Market Comparables

FNFA’s credit ratings are predicated on several factors. These factors include the strong

institutional and legislative framework, the expectation that FNFA is likely to receive

extraordinary government support, a solid governance and management structure, a rigorous

credit review process, strong interest and debt service coverage ratios, and several structural

protections that include:

- A mechanism to intercept revenue streams (‘Other Revenues’) that secure a Borrowing

Member’s loan payments and the deposit of these revenues, either directly or by an

intermediate account, into a segregated trust account (a ‘Secured Revenues Trust

Account’); - A Debt Service Reserve Fund (DRF) that is funded by a hold-back of 5% of the loan

advance, which serves as a layer of cross-collateral protection. Recent changes to the

First Nations Financial Management Act, FNFMA, now permit the holdback to vary

between 1-5%, but Management’s intentions are to stick with the practice of 5%.

(Additionally, rating agencies will be consulted ahead of a change, as the FNFMA

provides that the FNFA’s Board can only permit a lower hold-back if there are no adverse

rating consequences.). There is a requirement to replenish the DRF on a ‘joint and

several’ basis among all Borrowing Members who received financing from the FNFA, but

only within each borrowing stream (i.e. Property Taxes or Other Revenues); - A $10mln Credit Enhancement Fund (CEF) that was funded by the federal government.

The CEF was established to enhance the FNFA’s credit rating by being available to

temporarily offset any shortfalls in the Debt Reserve Fund. The CEF will be increased to

$30mln within the next year with a $10mln instalment this fall and another $10mln

instalment next spring; and - A legislative requirement to establish a sinking fund for each bond issue, which builds

based on the amortizing structure of the underlying loan.

The presumption of extraordinary federal government support is reasoned on the fact that it is

highly embedded in the overall program. The federal government has played an integral role

in establishing the framework for the FNFA through the enactment of federal legislation, the

establishment of federally operated boards engaged in processing First Nations community

groups into the program, ongoing oversight thereafter, and the provision of funds for the

Credit Enhancement Fund. With respect to the latter, the recent Federal budget explicitly

mentions ongoing intentions to build a better future for Canada’s Indigenous Peoples through

a wide range of initiatives as well as support for the First Nations Finance Authority to provide

$20mln over two years, beginning in fiscal 2016-17, to strengthen the Authority’s capital base.

While there is no explicit federal guarantee on FNFA bonds, the aforementioned factors

add up to a strong level of implicit and explicit support.

FNFA offers its borrowing members two types of loan facilities: Interim, and Long-Term

Loans. These facilities are discussed in more detail below. FNFA finances these loans

through a syndicated Bridge Financing Facility (the ‘Facility’) with three Canadian chartered

banks until it arranges long-term funding through a debenture offering.

The Facility is secured by first-ranking liens on all real and personal, corporeal and

incorporeal, present and future assets, including on all of the accounts of FNFA (including

accounts that hold the CEF and Debt Reserve Fund) and the rights of FNFA in the Secured

Revenues Trust Accounts and the Property Tax Accounts. FNFA is subject to non-financial

covenants, including a Material Adverse Change Clause and the ratings dropping to outside

of investment grade. The credit facility also requires the maintenance of two ratings, which

indirectly provides protections to bondholders as the debentures do not contain this provision.

Since inception of the Facility, there has never been a breach.

In February 2016, the security rankings of FNFA’s debentures were upgraded to rank

pari passu with FNFA’s $130mln secured line of credit. This was a major enhancement

for bondholders.

We note, however, that FNFA’s ratings are constrained by a number of rating factors which

are expected to abate over time. The rating agencies have cited FNFA’s relatively high – but

declining – volatility in profitability (previous losses from one-time start-up, and lower federal

grants and management fees), the geographic concentration of borrowers in the province of

British Columbia, which currently stands at 41% (July 2016), but is down from 65% in 2014,

as well as its short operating history. An improvement in any of these along with a stronger

liquidity profile could drive the ratings up. Conversely, a deterioration in the overall quality of

the loan pool or change in the FNFA’s framework and/or structural considerations for the

rating, including a reduction in government support, could put downward pressure on the

ratings. We are not expecting any changes to FNFA’s credit ratings in the near term, but

we believe there is more upside potential than downside risk to bondholders.

FNFA Borrowing Map

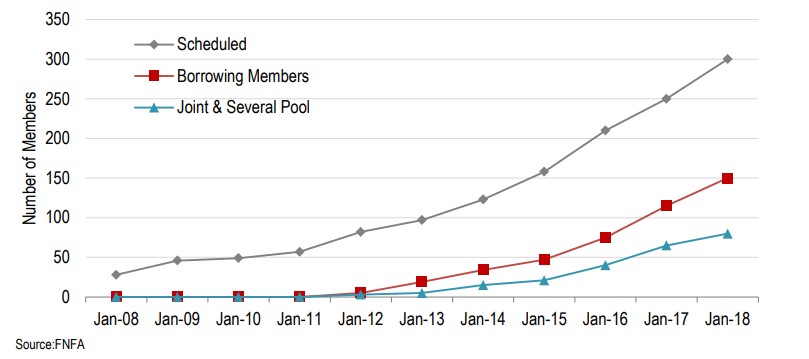

FNFA’s internal liquidity consists of approximately $2.2mln in cash and equivalents, $12.5mln

in investments representing amounts held in the Debt Reserve Fund and $10mln in the CEF,

which will grow to $30mln by next spring. Today’s level of internal liquidity of around $25mln is

just under 10% of outstanding debt, which is considered adequate for the ratings, but low for

higher rating categories. The liquidity metric will improve with additional deposits in the CEF.

External liquidity consists of the $130mln Bridge Financing Facility.

All in all, liquidity is considered adequate given the conduit nature of the intermediation

process where payments are intercepted from Borrowing Member revenue sources to service

outstanding debt and, therefore, liquidity needs beyond what is necessary for servicing debt

are minimal. Although FNFA’s borrowing powers are not restricted to providing loans to

Borrowing Members and it could borrow to finance working capital, historically the FNFA has

financed its operations through federal government grants and operating income from the

spread between what it borrows and lends at. On the lending side, FNFA’s mandate is only to

make loans to First Nations that have qualified as Borrowing Members.

In the past year, FNFA’s loan portfolio has grown from $140mln to $297mln, with an increase

in members from 23 to 34. In a year’s time, based upon the current loan portfolio plus the

expected disbursement of $130mln in additional loans prior to March 31, 2017, the DRF will

accumulate to approximately $21.5mln and the annual interest liability will be approximately

$12.4mln. With the CEF at $30mln, interest coverage will be over 4 times ($30+21.5/$12.4).

The FNFA plans to submit a request for a further $20mln to the CEF to expand it to

$50mln in 2017 in order to maintain the interest coverage ratio at or above four times

coverage (target interest coverage). Both Moody’s and S&P rate FNFA according to their

government-related entities methodology. With respect to S&P, the criteria falls specifically

under Rating Government-Related Entities: Methodology and Assumptions, published March

25, 2015. S&P gives FNFA a two-notch uplift from its Stand-Alone Credit Profile, or SACP,

rating of ‘bbb’ because it views the likelihood of FNFA receiving extraordinary government

support as ‘moderately high’. In a sovereign downgrade scenario – which we are not

anticipating – the methodology permits the Government of Canada rating to fall two notches

(i.e. from AAA to AA), without impacting FNFA’s ratings (all else remaining unchanged).

Under Moody’s Government-Related Issuers Rating Methodology (October 30, 2014),

Moody’s applies its Joint Default Analysis (JDA) framework to its analysis of Government Related Issuers (GRI) to explain the credit links between GRIs and their supporting central, regional, and local governments. This approach gives FNFA a two-notch uplift from Moody’s intrinsic Baseline Credit Assessment score of ‘baa2’ on a “strong likelihood of extraordinary support”. Moody’s framework incorporates the concepts of dependency and support which, in FNFA’s case, would also accommodate a multiple notch downgrade of Canada. The framework suggests a rating change only if Canada’s Aaa were to drop to A1, assuming everything else remains the same.

We caution that all rating agency methodologies are theoretical reference points and final

ratings are subject to the adjudication of the rating committees, but the aforementioned

analysis does suggest a strong degree of flexibility in a sovereign downgrade scenario.

Legislative Framework, Lending Approach, and Bondholder Protections

First Nations Finance Authority (the ‘FNFA’ or the ‘Authority’) is a non-share, non-profit

corporation established under Part 4, Section 58 of the First Nations Fiscal Management Act

(FNFMA, or the ‘Act’) which came into force on April 1, 2006. The FNFA is not an agent of

Her Majesty or a Crown Corporation.

First Nations Finance Authority’s head office is in Westbank, British Columbia. It operates

within the terms of reference embodied in the FNFA. It runs its operations from a single

location with credit adjudication done in-house as well as externally through a network of

advisors located across Canada.

The impetus for the development of the First Nations Finance Authority was based on

government policy research that concluded that a large gap exists in First Nations/Inuit

access to affordable private capital which is hindering their economic potential. This

conclusion was reached following a study that covered data from 1975 up to and including

2003.

First Nations/Inuit business financing access levels, trends and gaps all point to historical over-reliance on insufficient levels of government contribution capital and growth stalled at the early expansion phases for both the small and mid-sized ventures for lack of an organic connection to market capital. Correcting the situation is urgent and will require innovative ways to engage market sources of capital

beyond the limited leverage ability of existing sources of government help. From Access to Capital for Business: Scoping out the First Nation and Inuit Challenge, by Dr Dominique Collin, Waterstone Strategies and Michael Rice, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, May 2009.

First Nations Finance Authority fulfills an important role in reducing this gap. To facilitate

funding for First Nations communities, FNFA’s objectives are to monetize federal and

provincial revenue agreements with First Nations as well as First Nation’s own-source

revenues.

The First Nations Fiscal Management Act sets out the procedure for First Nations to become

‘Borrowing Members’ of the Authority and the requirements that must be fulfilled as part of the

borrowing process. It also gives the First Nations Finance Authority the powers to secure

financing for its Borrowing Members, and to issue securities.

In addition to facilitating access to funding for its Borrowing Members, the FNFA also

sponsors a pooled investment fund program for its ‘Investing Members’. Two pooled funds are

offered: the MFA Money Market Fund, and the MFA Intermediate Fund. The funds are operated and managed by the Municipal Finance Authority of BC.

It’s important to understand that participation in the FNFMA is optional. It was designed as an

optional piece of legislation to promote the continued economic development of participating

First Nations, but respecting their rights to self-government and self-determination.

While all First Nations have the authority to pass by-laws related to the taxation of land under

the Indian Act, the FNFMA offers an alternative and rigorous authority for First Nations to

collect property tax. By opting into the property tax system under FNFMA, First Nations are

better positioned to promote economic growth and capitalize on solid business relationships,

resulting in a better quality of life for community members.

The act enables First Nations to participate more fully in the Canadian economy and foster

business-friendly environments while meeting local needs by:

- strengthening First Nations real property tax systems and First Nations financial

management systems - providing First Nations with increased revenue raising tools, strong standards for

accountability, and access to capital markets available to other governments - allowing for the borrowing of funds for the development of infrastructure on-reserve

through a co-operative, public-style bond issuance - providing greater representation for First Nation taxpayers

The process to initiate participation in the FNFMA is via submission by a Band Council

Resolution to the Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs requesting that the band be

added to the schedule of the FNFMA. The process takes four to six months from the time the

Band Council Resolution is received, but recent amendments to the Act are expected to

shorten and streamline the process.

The FNFMA framework is supported by the work of the First Nations Finance Authority

(FNFA), First Nations Tax Commission (FNTC), and First Nations Financial Management

Board (FMB). The FNTC provides regulatory support to First Nations’ property tax

jurisdictions. The FMB sets standards for financial administration laws that it must review and

approve as well as conducts certification reviews of First Nations’ financial management

systems and financial performance.

An important protection to bondholders is that before a First Nation can borrow funds from the

Authority, the First Nation is required to make a Financial Administration Law regarding its

financial administration. The law must be approved by the First Nations Financial

Management Board (the ‘FMB’), the independent board established pursuant to the

Legislation, that reviews the law for compliance with the Legislation and the FMB’s standards.

The FMB’s standards are intended to support sound financial administration practices for a

First Nation.

A First Nation is required under the Legislation to obtain a Financial Performance Certificate

from the FMB before it can become a Borrowing Member of the Authority. A Financial

Performance Certificate will only be issued after the FMB reviews a First Nation’s financial

condition to determine if it complies, in all material respects, with the FMB’s standards. These

standards are comprised of seven financial ratios that are applied to the First Nation’s past

five years of audited financial statements. The ratios are intended to measure financial

capacity or risk of overall structural deficit; ability to meet short-term operating obligations;

ability to generate sufficient annual cash flows to maintain operations; ability to maintain a

sustainable level of capital investment; debt burden and overall insolvency; ability to manage

and execute budgets; and, the efficiency and stability in collecting property taxes. These

financial tests are intended to measure financial capacity or risk of overall structural deficit;

ability to meet short-term operating obligations; ability to generate sufficient annual cash flows

to maintain operations; ability to maintain a sustainable level of capital investment; debt burden and overall solvency; ability to manage and execute budgets; and, the efficiency and stability in collecting property taxes.

Financial Ratios

FMB examines the First Nation’s

past five years of audited

financial statements to assess

the following 7 financial ratios:

- Fiscal Growth Ratio (if a

decline greater than 5% occurs,

then test failed) - Liquidity Test (if a decline

greater than 10% occurs, then

test failed) - Core Surplus Test (weighted

average EBITDA must exceed

5% of current revenues)

4.Asset Maintenance

(maintenance/replacement must

exceed depreciation) - Net Debt Ratio (EBITDA is

equal to or exceeds 1.5 times

interest expenses)

6.Budget Performance (actual

expenses cannot exceed budget

more than 15%) - Property Tax Collection Rate

(prior 5 year average collection

rate must exceed 95%)

A First Nation must also obtain a Financial Management Systems Certificate within 36 months of receiving financing from the Authority (other than interim financing). Also, the Authority will require such a First Nation to obtain a Financial Management Systems Certificate prior to providing any loans subsequent to the loans contemplated by that First Nation’s initial borrowing law. A Financial Management Systems Certificate is more encompassing than a Financial Performance Certificate and will only be issued after the FMB reviews a First Nation’s financial management system to ensure it is operational and complies, in all material respects, with the FMB’s standards. These standards are intended to establish sound

financial practices for the operation, management, reporting and control of the financial management system of a First Nation.

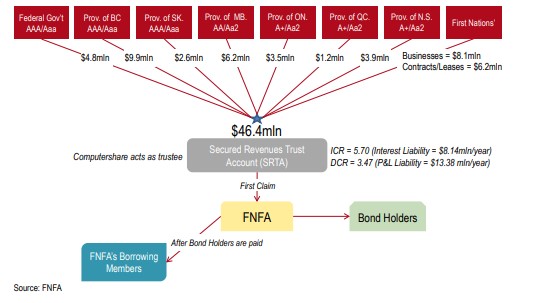

Claims to and collection of financial cash flows to service the FNFA’s debt is assured by several legal and structural protections.

Direction to Pay | Intercept

The Authority uses a mechanism to intercept revenue streams (‘Other Revenues’) that secure a Borrowing Member’s loan payments. As required by the Legislation, each Borrowing Member irrevocably instructs third parties paying Other Revenues that secure a loan to pay those revenues, either directly or by an intermediate account, into a trust account (a ‘Secured Revenues Trust Account’) maintained by Computershare Trust Company of Canada (the SRTA Manager’) throughout the period of the loan. Under the terms of the Secured

Revenues Trust Account, only the Authority (and not the applicable Borrowing Member) is entitled to instruct the SRTA Manager on the allocation and payment out of amounts from the Secured Revenues Trust Account and all payments to the Authority from the Secured

Revenues Trust Account are made by the SRTA Manager. This ensures that amounts due to the Authority, including any amounts required to replenish the Debt Reserve Funds, are paid before any remaining amounts are paid to the Borrowing Member.

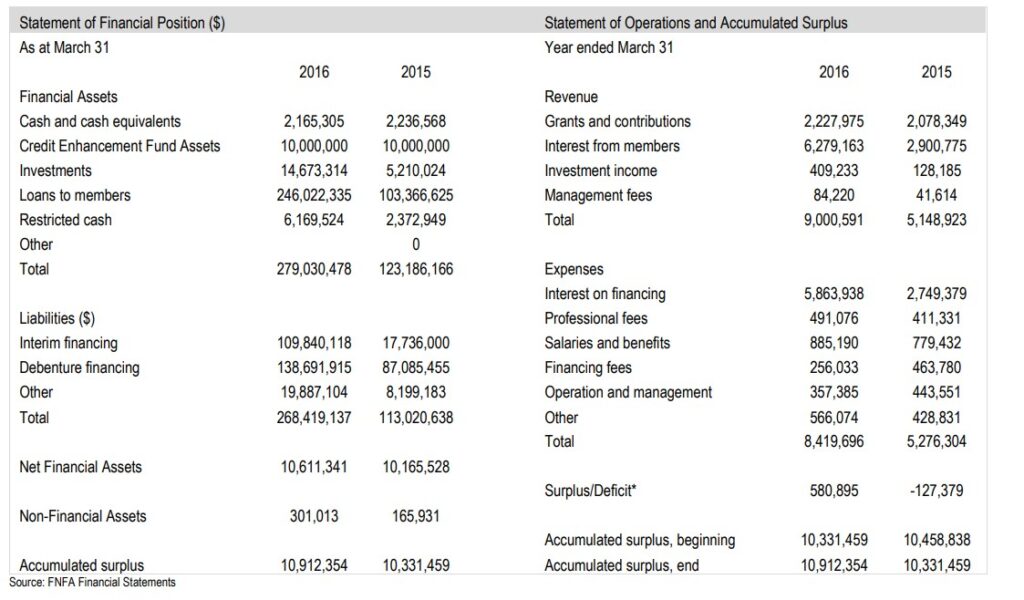

Intercepted Revenues Supporting FNFA Loans

Where the Other Revenues comes from a contract or an agreement, generally, the full

amount of the Other Revenues is paid into the Secured Revenues Trust Account. Where the

Other Revenues is from a Borrowing Member’s owned business, the amount collected into

the Secured Revenues Trust Account is greater than that needed to fulfill loan payments. The

Authority ensures the Secured Revenues Trust Account collections are equal to or greater

than a debt coverage ratio. Each revenue stream is evaluated upon criteria such as payor

risk, duration of stream, stability, etc. and has a debt coverage ratio applied to it.

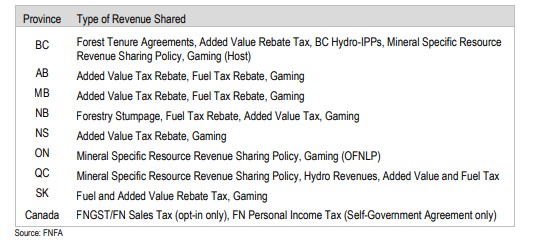

Revenue Sharing by Province

Priority of Claims

In the event that a Borrowing Member becomes insolvent, the Legislation (section 78)

provides that the Authority has priority over all other creditors of the Borrowing Member (other

than the Crown) for any amounts payable by the Borrowing Member to the Authority in

connection with a loan secured by Other Revenues (as authorized under an agreement

governing a Secured Revenues Trust Account) or under the Legislation.

The Authority does not rely on provincial Personal Property Security Act (‘PPSA’) legislation

to perfect its security. To prevent inconsistent priorities, PPSA legislation generally excludes

from its application security given by another enactment. Moreover, the Indian Act (section

88) provides that provincial laws of general application (such as PPSA legislation) are not

applicable to or in respect of Indians to the extent that those laws are inconsistent with the

Legislation.

Sinking Fund

The Authority is required by the Legislation to maintain a Sinking Fund to fulfill its repayment

obligations for each bond issue. All principal repayments by Borrowing Members on loans

from the Authority financed with proceeds of bonds are placed in a Sinking Fund for such

bonds.

Debt Reserve Fund

The Authority is required by the Legislation, in connection with providing loans to Borrowing

Members, to establish a Debt Reserve Fund. The Authority is required to withhold between

1% and 5% (the Authority currently withholds 5%) of the amount of any loan secured by

Borrowing Members using Other Revenues and deposits that amount into the Other

Revenues Debt Reserve Fund. If at any time the Authority has insufficient funds from

Borrowing Members that have received financing secured by Other Revenues to make

payments to bondholders, including Sinking Fund contributions, such payments are to be

made from the Other Revenues Debt Reserve Fund.

If payments from the Other Revenues Debt Reserve Fund reduce its balance by 50% or more

of the total amount contributed by Borrowing Members, then the Legislation provides that the

Authority must (and may where the balance is reduced by less than 50%) require all

Borrowing Members who contributed to the Other Revenues Debt Reserve Fund to pay amounts sufficient to replenish that fund. As a consequence of this replenishment mechanism, Borrowing Members that have received financing secured by Other Revenues are potentially liable for, and support, the debt obligations of any defaulting Borrowing Members that have received financing secured by Other Revenues. Amounts due to the Authority to replenish the Debt Reserve Fund may be drawn from the Secured Reserve Trust Account of a Borrowing Member, which collects an amount above what is required to service regular debt payments.

Credit Enhancement Fund

In accordance with the Legislation, the Authority has established a Credit Enhancement Fund

of $10mln to support the Debt Reserve Funds in making payments to bondholders. This fund

may be used by the Authority to temporarily off-set any shortfalls in the Debt Reserve Funds.

On March 22, 2016, the Government of Canada, as part of its 2016 budget, announced that it

proposes to provide $20mln over two years, beginning in the Government of Canada’s 2016-

2017 fiscal year, to strengthen the Authority’s capital base. Any such amounts received by the

Authority from the Government of Canada will be added to the Credit Enhancement Fund.

Investment Authority

The Legislation provides that amounts in Sinking Funds, Debt Service Reserve Funds and the

Credit Enhancement Fund can only be invested in certain eligible investments. The Authority

may only invest in: (a) securities issued or guaranteed by Canada or a province; (b)

investments guaranteed by a bank, trust company or credit union; and (c) deposits in a bank

or trust company, or non-equity or membership shares in a credit union. With respect to

Sinking Funds, the Authority may also invest in (a) securities of a local, municipal or regional

government in Canada and (b) securities of the Authority or a municipal finance authority

established by a province, if the day on which they mature is not less than the day on which

the security for which the sinking fund is established matures.

The Authority has adopted a formal Investment Policy not to invest funds in a Sinking Fund for

deposits in a trust company, or non-equity or membership shares in a credit union.

The Investment Policy has incorporated the following constraints:

- DRF investments should attempt to provide sufficient liquidity through cash or cash

equivalents to permit the FNFA to meet up to one year of sinking fund and interest

payments for all outstanding debentures. - Sinking Fund investments should attempt to preserve capital and approximately match the

debenture maturity date. However, it is understood that prudent investment management

may entail some investments matching the loan term to the Borrowing Members instead of

the debenture maturity term where these loan terms are for a longer period than the

debenture (i.e. loans that will need to be refinanced over their term).

The Investment Policy has established guidelines with respect to credit quality and

diversification.

Intervention Mechanism

If a Borrowing Member that has received financing secured by Other Revenues fails to make

a payment to the Authority under a borrowing agreement, or fails to pay a charge imposed by

the Authority in connection with replenishing a shortfall in the Other Revenues Debt Reserve

Fund, the Authority can require the FMB to either impose a ‘co-management arrangement’ in

respect of that Borrowing Member’s Other Revenues, or assume ‘third-party management’ of

that Borrowing Member’s Other Revenues. If the FMB assumes ‘third-party management’ of

the Borrowing Member’s Other Revenues, the FMB has exclusive right to, among other

things, act in place of the Council of that Borrowing Member in relation to assets of that

Borrowing Member that are generating Other Revenues.

In four years of FNFA loans, no third-party management or co-management arrangement has

ever been initiated as a result of a Borrowing Member failing to make payments to the FNFA.

It is highly unlikely in the future for any of FNFA’s clients since revenue streams are

irrevocably intercepted for the full loan term from the payor source prior to loan release and

the majority of these loans are payments from provincial governments or crowns. Hence, a

failure in the intercept arrangements and/or a default of a province (or crown) would be a

necessary scenario for this to happen. We highlight Canada’s strong AAA rating and the

senior ratings enjoyed by Canada’s provinces. We also point out that FNFA does not have

any single revenue stream clients.

In a revenue intercept scenario, FNFA staff would immediately contact the payor for an

understanding. If the payor still refused to pay into the revenue intercept account with the

SRTA manager, then a court action would be started.

The Financial Management Board, under the Legislation, has full authority to become the

manager/treasurer over all of a Borrowing Member’s Other Revenues, including Other

Revenues that currently do not secure loans by the FNFA. The FMB can use that authority to

ensure amounts due to the FNFA are repaid. The FMB’s authority is under the Legislation,

rather than contractual, which makes enforceability very strong. FMB staff do not do this

intervention. FMB has an agreement with a national accounting firm that is an experienced

intervenor to handle this function.

There is only one co-management arrangement existing in FNFA’s portfolio. The coarrangement is with St. Theresa Point, a band in Manitoba. The co-arrangement existed prior to joining the program. The co-arrangement was not related to failure to pay loan service or any liabilities, but rather related to the band asking for help in the areas of accounting and finance. The revenues servicing FNFA’s loan to St. Theresa Point are coming directly from the Province of Manitoba and the Debt Service Coverage Ratio (P&I) is strong at 6.28 times. The band is in a strong operating surplus position.

Recent Changes to the FNFMA

Legislative and regulatory amendments to the FNFMA came into force on April 1, 2016

stemming from recommendations and consultations with the FNFA, FMB and FNTC to

improve the regime’s overall framework. The changes are expected to have a positive impact

on facilitating entry of more First Nations, accelerate bond issuance and strengthen investor

confidence.

Notable enhancements include:

- Allowing payments in lieu of taxation through a new fiscal power to collect fees for water,

sewer, waste management, animal control, recreation, transportation and other similar

services. - Giving First Nations the power to recover costs of enforcement, including the costs for

seizure and sale of taxable property. - First Nations’ Financial administration laws must meet higher requirements set by the

Financial Management Board (FMB) on an ongoing basis and these laws cannot be

repealed unless they are replaced by laws approved by the FMB. - Tougher requirements on management of local revenues including their maintenance in

separate accounts from all other First Nations moneys as well as separate financial

reporting and auditing requirements, unless permitted by FMB to include as part of audited

annual financial statements. - Clarification of the separation and distinction of Debt Service Reserve Funds (DRF) for loans secured by property tax revenues and loans secured by other revenues. The FNFA has been given flexibility to withhold between 1-5% of the loan amount, depending on the circumstances and in accordance with regulations. Initially, the withheld rate was set at 5%, at a higher threshold than observed in municipal borrowing practices. Some flexibility was granted with this change, but the Authority’s practices are expected to remain unchanged. Clarification was also given that only Borrowing Members who have received financing can be called on to contribute to or replenish a DRF and only the DRF for their borrowing stream. There are two streams, one for Property Taxation and the other for Other Revenues. In each stream, however, Borrowing Member obligations to replenish are joint and several. Enhancement to the Act also established that the FNFA’s priority over other creditors of a First Nation in the event of an insolvency arises from the date the borrowing member has received financing from the FNFA, thus strengthening its priority.

- The ability to invest sinking fund proceeds in FNFA bonds to reduce net funding costs,

although, from a ratings perspective, this does not reduce the total amount of outstanding

debt. The increased flexibility will also allow FNFA to manage its bonds in the secondary

markets. - Introducing a mechanism for repayment to the Credit Enhancement Fund (CEF), within 18

months, where the CEF has been used to replenish a DRF.

Credit Underwriting Process and Experience

This credit history of lending to First Nations through the First Nations Finance Authority is

short as it only came into existence in 2006. More history can be found in the bank lending

sector of making loans on First Nations reserves. There has not been a recorded loan default

by a First Nation since at least 1970. There have been only a few known cases in the past

where there was difficulty in collecting but, in those cases, either the financial institution failed

to follow its own normal lending criteria or failed to properly contractually secure its position

including the ‘Redirection to Pay’. Banking lenders have often noted strong moral suasion and

moral obligation to fulfill loan repayment requirements due to the closeness of First Nations

Communities and a sense of duty and honour. We highlight that FNFA’s experience to date

shows a meaningful percentage of First Nations making payments ahead of schedule. In

FNFA’s 2016 Annual Report, the level of prepayments is shown at $5.8mln, almost a full

year’s interest payment ahead.

The financial strength and economic potential of First Nations communities continues to

evolve in a constructive manner as evidenced by the number of First Nations that are

participating in the First Nations Fiscal Management Act (FNFMA) and the growth in their

own-source revenue. A total of 13 First Nations opted to participate in the FNFMA shortly after

it came into force in April 2006 (i.e. original members). Today, there are 200 First Nations

scheduled versus 634 First Nations across Canada.

It is estimated by Dr Dominique Collin of Waterford Strategies that own-source revenues

accounted for about one-third of total revenues of participating First Nations combined, or

$2.6bln, in Fiscal 2014-15. This is up from about 16% 10 years ago.

FNFA’s mandate allows First Nations to access ‘Long-Term Loans’ or financing that is

supported by two types of revenue streams: property taxation revenues and other revenues. It

also offers ‘Interim Financing Loans’ to cover costs during construction or bridge financing

until FNFA issues its next debenture. FNFA has yet to receive a loan application which

falls under the property taxation revenue stream, although the legislation was

originally contemplated for this type of borrowing.

Long-term financing or lease financing of capital assets is made for the provision of local

services on reserve bands. Short-term financing for operating or capital purposes is made

either in accordance with the stated purposes of paragraph 5(1)(b) of the FNFMA which

relates to spending supported by Property Tax Revenues or to refinance short-term debt

incurred for capital purposes. The Other Revenues Regulation outlines spending purposes for Other Revenues (i.e. infrastructure, social and economic, land purchases, etc.).

FNFA’s ratings are constrained to the upside by a lack of diversity in size, credit quality and

geographic diversification of its loan portfolio. Rating agencies have taken a cautious

approach to rating the FNFA given its short operating history, rapid loan growth and loan

concentration issues; but these overall characteristics are expected to strengthen over time as

the program grows and expands across Canada. FNFA projects its loan portfolio to grow

from about $297mln today to over $1.2bln by 2021 (Loan Growth: 2017 projected to

$385mln; 2018 $515mln; 2019 $715mln; 2020 $955mln; 2021 $1.225bln).

As a matter of practice to ensure adequate diversification and to support its strong credit

ratings, the FNFA has reduced its individual loan exposures with the goal of keeping

concentrations below 20%. In 2014, Membertou (largest borrower) was 24.59% of the loan

pool. In July 2016, it was down to 11%.

FNFA aspires to stronger geographical distribution as currently its members are located in

only eight provinces. FNFA Board Policy for minimum Debt Coverage Ratio (‘DCR’) of its

individual Borrowing Member loans is set to at least 1.23 times, but its members are operating

at much higher thresholds. While Borrowing Members must meet stringent requirement to

participate in the program already, the Authority limits their borrowing to 75% of their

calculated borrowing capacity (75% Rule). Should a member want their loan amount to

exceed 75%, the FNFA staff do a further review of financial information/revenue stream

documents before granting such loan privileges.

Borrowing Member loans are all in Canadian dollars and are amortizing, but have loan terms

that expire ahead of full amortization and therefore must be refinanced. FNFA’s borrowings

are done in Canadian dollars, hence there is no foreign exchange risk assumed.

With respect to the amortization of client loans and refinancing risk, 90% of client loans have

repayment terms that extend beyond FNFA’s debenture maturity in 2024. These clients are

given a choice to lock-in rates with an interest rate swap for their full loan term, but none have

taken this since Supreme Court decisions in respect of First Nations entitlements have

caused revenues to grow much faster than the national average of revenue growth for First

Nations (up 2.5 times since 2005) and, therefore, First Nations generally want the option to

fully payout their loans in 2024. Of those First Nations that do not payout the loan and need to

refinance, because FNFA operates under a sinking-fund approach with debt service collected

to include principal along with interest, any amounts refinanced would approximate 50% of the

original balance. Thus, interest rates would have to double to maintain the same annual

interest commitments for FNFA’s clients.

Currently, the majority of FNFA’s intercepted revenues are from federal and provincial grants

or revenue sharing arrangements, accounting for approximately 70% of total intercepted

revenues. Some risks exists with respect the cyclicality of these revenue streams or other

credit factors, but in general, these are well secured. As FNFA’s intercepted revenue stream

contains a significant percentage of other revenues (i.e. non-government), normal credit risk

factors apply. Today, business revenues include lease contracts from owned buildings that

are anchored by strong national tenants. There is also a gaming business. The only existing

pipeline and utility related revenues are associated with BC Hydro, Hydro Quebec and Hydro

One which are provincial crowns.

In 2014-2015, the FNFA’s intercepted revenues had an Interest Rate Coverage Ratio (‘IRC’)

of 6.3 times (i.e. revenues intercepted were 6.3 times greater than the debenture’s interest

liability). Approximately 75% of these revenues were from federal/provincial revenue sharing

agreements; the balance being contractual revenues, lease agreements and established

Band businesses. At the time of the recent debenture issues, the percentage has fallen from

75% to 67%, but the coverage ratios have improved. Intercepted revenues are from

Fed/Provincial sources alone have a Debt Coverage Ratio (‘DCR’) of 2.25 times annual debt

service.

Interest Rate Coverage Ratio (‘IRC’) and Debt coverage Ratio (‘DCR’)

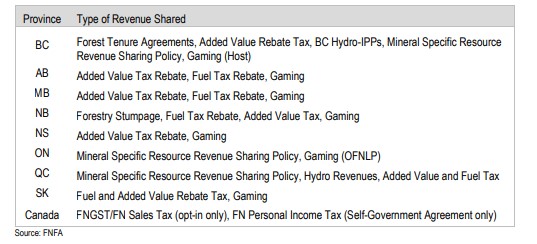

FNFA Borrowing Members, Future Projections

Financial Reporting and Transparency

Canada’s accounting architecture is founded on the work of several independent, volunteer

bodies to establish authoritative standards of recommended or required practice. These

bodies include the Public Sector Accounting Board (PSAB). PSAB issues standards and

guidance with respect to matters of accounting (Public Sector Accounting Standards – PSAS),

as well as financial reporting recommendations of good practice (Statements of

Recommended Practice – SORPs). Their work is to serve the public interest by strengthening

accountability in the public sector. The public sector refers to governments, government

components, government organizations, and government partnerships. While compliance with

PSASs is voluntary by the sovereign (Federal Government of Canada) and sub-sovereigns

(Provinces), adherence to the PSAB requirements is legally required at the municipal level

under various municipal acts. As it pertains to First Nations and their right to self-govern,

reporting and transparency is voluntary by opting to participate under the First Nations

Transparency Act and report under PSAB.

Successful monitoring of participating First Nations by the First Nations Finance Authority is

dependent on access to financial information. The First Nations Transparency Act requires

that each First Nation to which the Act applies publish on its Internet site, or cause to be

published on an Internet site, the following documents within 120 days after the end of each

financial year:

- its audited consolidated financial statements

- the Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses

- the auditor’s written report respecting the consolidated financial statements; and

- the auditor’s report or the review engagement report, as the case may be, respecting the

Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses

These documents must remain accessible to the public on an internet website, for at least 10

years.

The Act further states that the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development must

publish these same documents on the departmental website “without delay after the First

Nation has provided him or her with those documents or they have been published.”

First Nations do not have interim reporting requirements.

With respect to the First Nations Finance Authority, it has to file an annual report before July

31 of each year, within 120 days after year end (Section 88 of the Act). There are no interim

reporting requirements, but Management is actively engaged in providing investors with

regular updates.

First Nations Finance Authority

Financial Reporting and Transparency

Canada’s political system is a Westminster-style democracy with a federal system of

parliamentary government. Canada is a constitutional monarchy in which the Queen or King is

recognized as the head of state. Since February 6, 1952, the Canadian monarch has been

Queen Elizabeth II, who is represented by the Governor General. The federal system is a

union of partially self-governing regions, known as provinces (i.e. sub-sovereigns), under a

central (federal) government (i.e. sovereign) where there is a division of power between the

federal government and the provinces.

Canada has three main levels of government: federal, provincial (and territories), and

municipal. The Constitution Act, signed in 1867, defines their respective powers, some of

which are shared. While territories and municipalities have their own governments, they are

not considered sub-sovereigns as they have no legislative authority to determine their powers

and responsibilities. The responsibilities of the three territories are granted to them by the

federal government while the responsibilities of municipal governments are granted by their

respective provincial governments.

Under the constitution, the federal government has jurisdiction over: national defence, foreign

affairs, employment insurance, banking, federal taxes, the post office, fisheries, shipping,

railways, telephones, pipelines, aboriginal lands and rights, and criminal law. The federal

government re-distributes wealth among the provinces through a system of equalization

payments (i.e. extra money) given to provinces that are less wealthy, thus ensuring that the

standards of health, education and welfare are the same for every Canadian.

The provinces have powers over: direct taxation, health care, prisons, education, some

natural resources, marriage, road regulations and property and civil rights. Power over

agriculture and immigration is shared between the federal and provincial governments.

Municipalities are responsible for areas such as libraries, parks, community water systems,

local police, roadways and parking, receive their authority from the provincial governments.

Across the country there are also band councils, which govern First Nations communities.

These elected councils are similar to municipal councils and make decisions that affect their

local communities and operate under a framework of right to self-government or self determination.

Aboriginal self-government is specifically referred to governments designed, established and

administered by Aboriginal peoples under the Canadian Constitution through a process of

negotiation and, where applicable, the provincial or territorial government.

History of Canada’s First Nations

According to the last census (2011), there were approximately 1.4 million indigenous people

living in Canada (status and non-status), representing just over 4% of Canada’s 34.3 million

population at that time. The indigenous count included 851,000 First Nations, 451,000 Métis,

and 59,000 Inuit. A Canadian status indigenous person is a legal term referring to any First

Nations individual who is registered with the federal government or a band which signed a

treaty with the Crown. Many indigenous First Nations Canadians live on reserves, an area of

land in which the legal title is held by the Crown, but is set apart for the use and benefit of a

First Nations band.

First Nations lived in Canada for thousands of years before the arrival of the Europeans in the

eleventh century. These First Nations were able to satisfy their material and spiritual needs

through the resources of the natural world surrounding them. Historians tend to group

Canada’s First Nations into six main geographic areas of the country as it exists today:

- Woodland First Nations, who lived in dense boreal forest in the eastern part of the country

- Iroquoian First Nations, who inhabited the southernmost area, a fertile land suitable for

planting corn, beans and squash - Plains First Nations, who lived on the grasslands of the prairies

- Plateau First Nations, whose geography ranged from semi-desert conditions in the south,

to high mountains and dense forest in the north - Pacific Coast First Nations, who had access to abundant salmon and shellfish and

gigantic red cedar trees used for building houses - First Nations of the Mackenzie and Yukon River Basins, whose harsh environment

consisted of dark forests, barren lands, and the swampy terrain known as muskeg

Within each of these six areas, First Nations had very similar cultures, largely shaped by a

common environment. They tended to function on the basis of a complex system of

government based on democratic principles.

Today, the relationship between First Nations and the government is based on a broad

collection of treaties covering pre-confederation, peace, and friendship treaties, as well as

post-confederation or numbered treaties. In more recent history, there are also ‘Modern

Treaties’, with the first one historically documented in the mid-1970s. Modern treaties have

been entered into to satisfy comprehensive or specific land claim rights of Aboriginals that

were not addressed by previous treaties, or by other legal means.

Aboriginal peoples, under the treaties, are recognized as the descendants of the original

inhabitants of North America. The Canadian Constitution recognizes three groups of

Aboriginal people with unique heritages, languages, cultural practices and spiritual beliefs.

These are the Indians, Métis and Inuit. The term ‘First Nation’ came into usage in the 1970s

and is widely used today to replace the word ‘Indian’ or ‘band’, although it is not a term that is

legally recognized.

An historic Canadian settlement in the right to self-government was achieved in 2006, after 16

years of legal negotiations challenging the authority of the federal government. The

agreement resulted in the transfer of $350mln in energy royalties to the Samson Cree. The

money was placed in an independent trust fund (‘Kisoniyaminaw Heritage Trust’). It was the

first time an Indian group was successful in seizing its own moneys and setting up a trust to

which it had power of trustee and control of its own assets. The settlement also saw the

removal of the federal government as trustee of all energy royalties for the Samson Cree and

Ermineskin, two bands located on the Hobbena reserve in central Alberta.

“Control of our heritage trust moneys is a major step forward for the present and future

generations of Samson Cree Nation members, and an important recognition of our Treaty 6

rights,” said Chief Victor Buffalo.

Additional Sources

- Government of Canada, FNFMA Act

- FNFA website

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada

- The Canadian Press